Sombrilla

Sombrilla International Development Society is an Alberta-based organization that partners with communities in Latin America to empower them to assert their democratic, economic, cultural, and social rights.

See us on the Together Alberta Map

I first visited El Salvador in 1997, as a project monitor for a small Alberta-based NGO. Our work took us to the small town of El Mozote in the northeast, near Honduras. Upon arrival, our group was greeted by a desolate scene: a barren town square, a small horse tied to a tree, and a church much too large for the surrounding community. Next to the church was a lonely drying line bearing the clothes of young children.

In 1981, El Mozote was the site of one of the largest massacres to take place in Central America, part of a “scorched earth” strategy by the Salvadoran military to remove villagers who supported the insurgent groups fighting for land reforms and other human rights that the ruling oligarchy had denied. Almost a thousand villagers were killed, many of them young children. The bones of many children were found beneath the site of that very church.

Following the massacre, these atrocities were covered up by the Salvadoran Army, with support from the United States government. Then, in 1993, the Salvadoran government passed the General Amnesty Law, which made it illegal to investigate, prosecute, or jail people for war crimes or human rights violations, such as those committed at El Mozote. For the most part, evidence of past crimes was buried until July 2016, when the Constitutional Court in El Salvador declared the General Amnesty Law unconstitutional, opening a way for the story of El Mozote to be fully uncovered.

“We are obligated to open spaces for collective memories to live, and to guide us into a future where justice may be restored.”

In 2010, I travelled back to El Salvador, where I met a man named Henry Chicas, who as a child had lived in a region near El Mozote that was severely affected by the civil war. Today, he is a beneficiary of a partnership between the Alberta-based Sombrilla International Development Society and the Christian Based Community of El Salvador Perquin (CEBES Perquin) — an organization that confronts the civil war’s legacy while promoting peace and justice. CEBES Perquin also contributes funding for educational scholarships and programs that provide training for post-secondary students to encourage them to become involved in their local communities.

Henry is among many young community leaders in El Salvador who, supported by Albertans, have completed professional degrees and brought their expertise in business, agronomics, psychology, and law to promote both human rights and the SDGs within their communities. Henry now uses his accounting skills to document the victims of the massacre so that the government can properly compensate family survivors. He also supports community members to develop local microenterprises, giving the families of victims an opportunity to make a living wage.

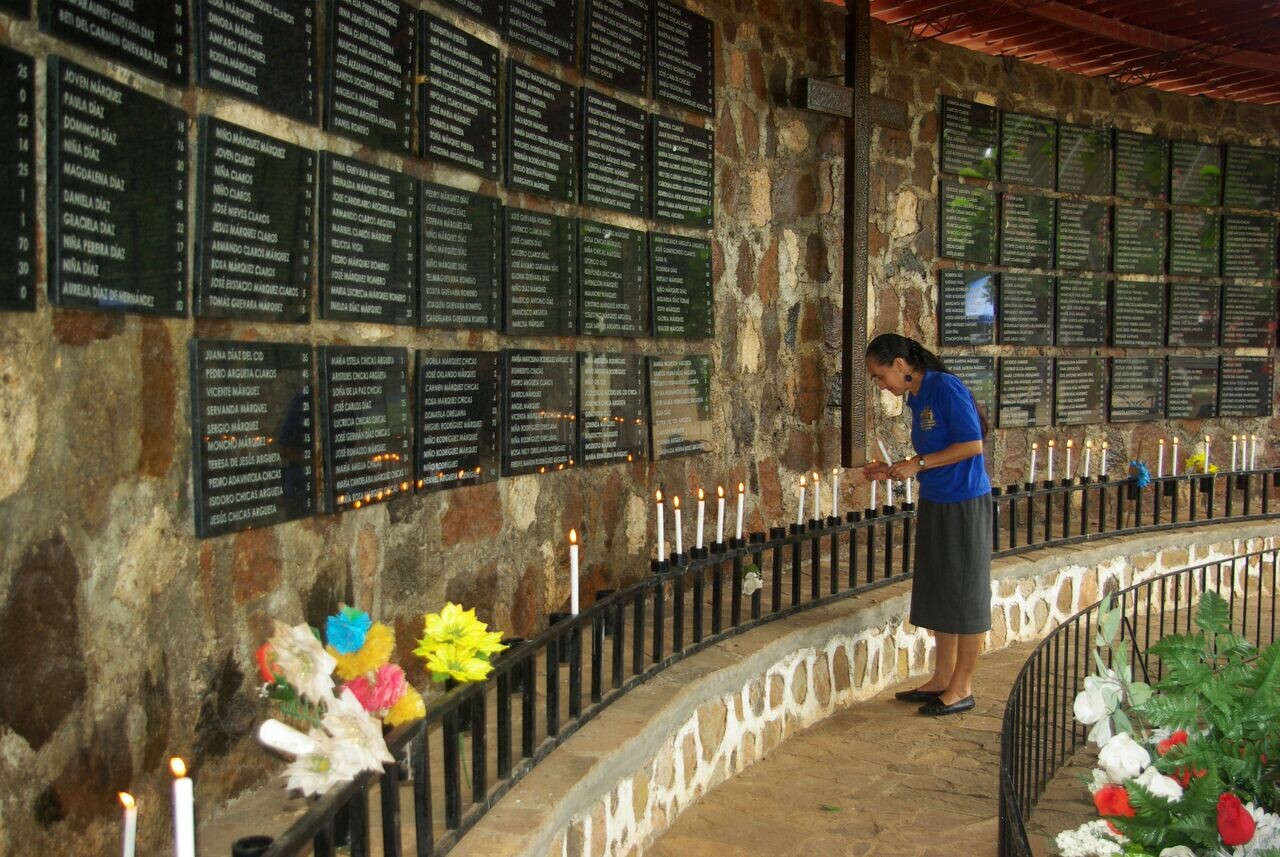

As for the village of El Mozote — it has been reborn. With the help of international contributions, a large monument, entitled “Peace and Reconciliation,” has been erected, and a spiritual centre and chapel are under construction. The streets bustle with local business, as well as travellers interested in social justice and the study of liberation theology. That large church is filled with the children whose clothes I saw drying — adults now, and willing partners in the reconstruction of a better and more just world.

How the atrocities of El Mozote were once forgotten demonstrates how the interests of the powerful can override the rights of the voiceless and vulnerable. In Canada, we only have to turn to our country’s disastrous experience with residential schools to understand how these forces undermine human rights. Until recently, many Canadians didn’t know about our residential schools. This history was all but erased. However, recent work towards reconciliation, including the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, has brought this past to light and has opened a door for justice and reparations.

Henry says his wish is to “see a strong practice of remembering history to guide the future so the tragic events that happened become an inspiration to build strong, sustainable communities.”

In El Salvador, as in Canada and around the world, dark or uncomfortable chapters of history are sometimes made to disappear from collective memory. They are made to disappear because to remember them demands that we think critically about the collective moral debt we must recognize and redress. Because this debt belongs not only to the state, but to the entire nation, we are obligated to open spaces for collective memories to live, and to guide us into a future where justice may be restored.